Innovation Cycles In An Age Of AI

AI is compressing the timelines that once defined how companies rise and fall.

Welcome to the latest edition of The API Economy. Thanks for being here.

To support the API Economy, join the 11,267 early, forward-thinking people who subscribe for insights on the forefront of technology, crypto, AI, and other emerging trends.

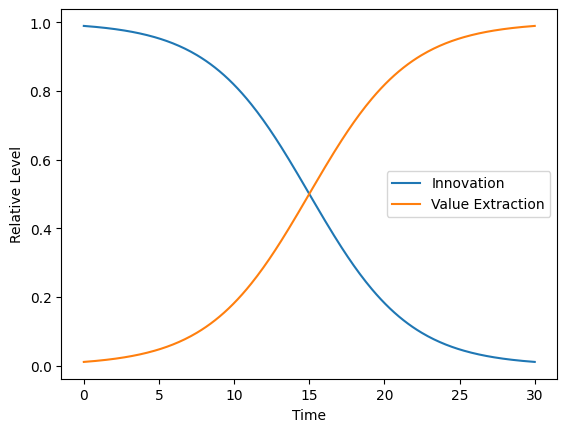

The great products of one generation have a strange habit of becoming the villains of the next.

Products that begin as rebellions against the establishment often grow into the establishments of tomorrow, gradually shifting from creating value to extracting it. The interface remains familiar, the brand stays powerful, but the product no longer feels like it is working on your behalf.

You see this everywhere. Open YouTube, and you are pushed toward another subscription or forced to sit through so many ads that the content barely feels worth your time. Trading apps that once promised openness and accessibility now charge fees comparable to the institutions they set out to challenge. The iPhone, once defined by step-change improvements, has felt largely unchanged across the past several generations.

These common patterns aren’t driven by a lack of imagination or poor execution. They are driven by incentives.

Early in a company’s life, the goal is simple: build something compelling enough to earn user adoption.

Speed matters. Creativity matters. Product quality matters. Over time, those priorities shift. Growth slows. Markets mature. The company becomes large enough that stability and revenue optimization begin to outweigh experimentation and improvement.

Scale changes behavior. Large systems reward predictability and punish risk.

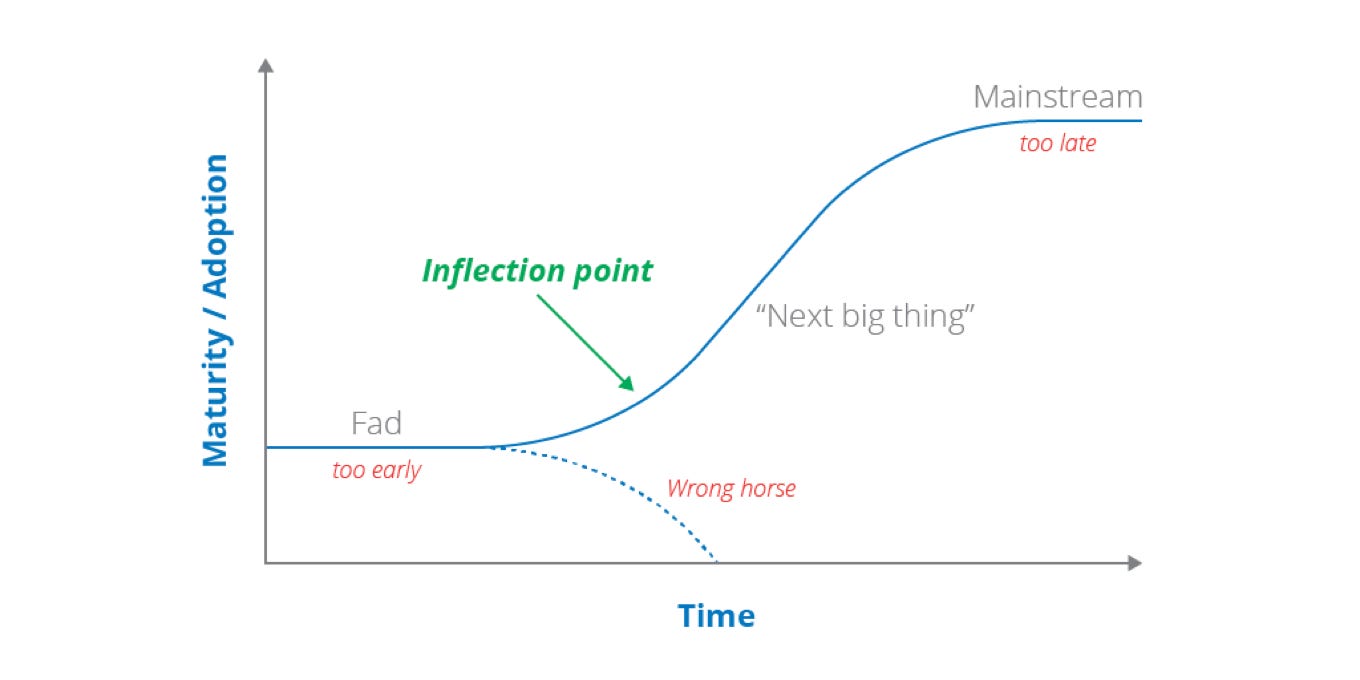

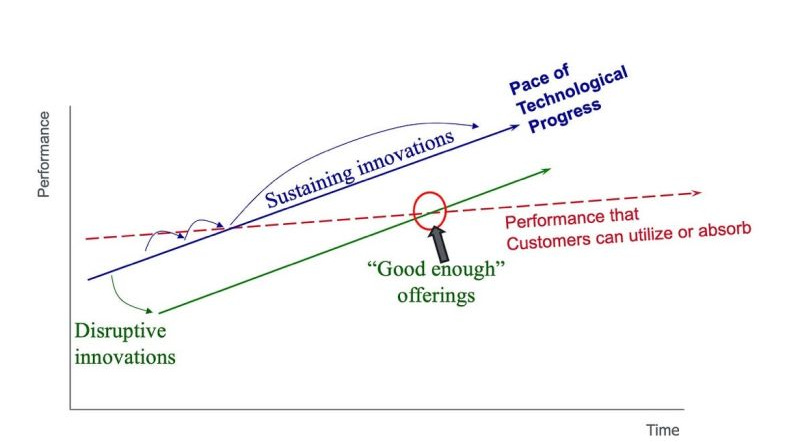

The Innovator’s Dilemma

Clayton Christensen described the struggle for big companies to build new things of value as the innovator’s dilemma. Successful companies are rewarded for improving what already works. They listen closely to their largest customers. They invest in products with clear returns. They avoid initiatives that threaten existing revenue.

Over time, incumbents become excellent at optimization and weak at exploration.

The problem is that meaningful innovation rarely looks attractive at the beginning. New ideas start small. They serve marginal users. They generate little revenue. From inside an established organization, they appear risky and distracting. They compete with proven products for attention and resources, and often undermine the economics of the current business.

As Chris Dixon has noted, many breakthrough technologies were first built by hobbyists operating outside the center of the market. These ideas did not emerge because they were obviously valuable. They emerged because they were allowed to exist without needing immediate justification.

Startups operate under different rules than large businesses. They can build products driven by curiosity rather than certainty. They can pursue narrow use cases. They can accept ambiguity. They optimize for possibility rather than efficiency. That freedom allows new platforms and tools to emerge beyond the reach of incumbent incentives.

This is why major shifts in technology rarely come from market leaders. Over time, every successful product becomes something that must be protected. Once protection becomes the priority, innovation slows.

Most incumbents historically have failed here because the cost of experimentation is immediate and visible, while the cost of stagnation is delayed and diffuse. Quarterly incentives reward efficiency and punish optionality.

Over time, organizations become very good at protecting what they have and very bad at imagining what they could become.

When experimentation becomes cheap and production timelines shrink, protection weakens. Capital, talent, and attention flow toward better products rather than better defensive tactics.

Large companies have struggled to match the speed of startups operating at the edges of the market. Reacting to new ideas often took years, especially when those ideas served small or underserved users. By the time incumbents responded, the opportunity had already moved on most of the time.

But with AI compressing these development cycles and enabling engineers to do more with less, speed is no longer an exclusive advantage of startups. The gap is narrowing, and incumbents that adapt their incentives can now move faster than ever before.

There Are Cathedrals Everywhere For Those With The Eyes To See

For most of human history, progress advanced slowly and unevenly. Breakthroughs were rare and often separated by generations.

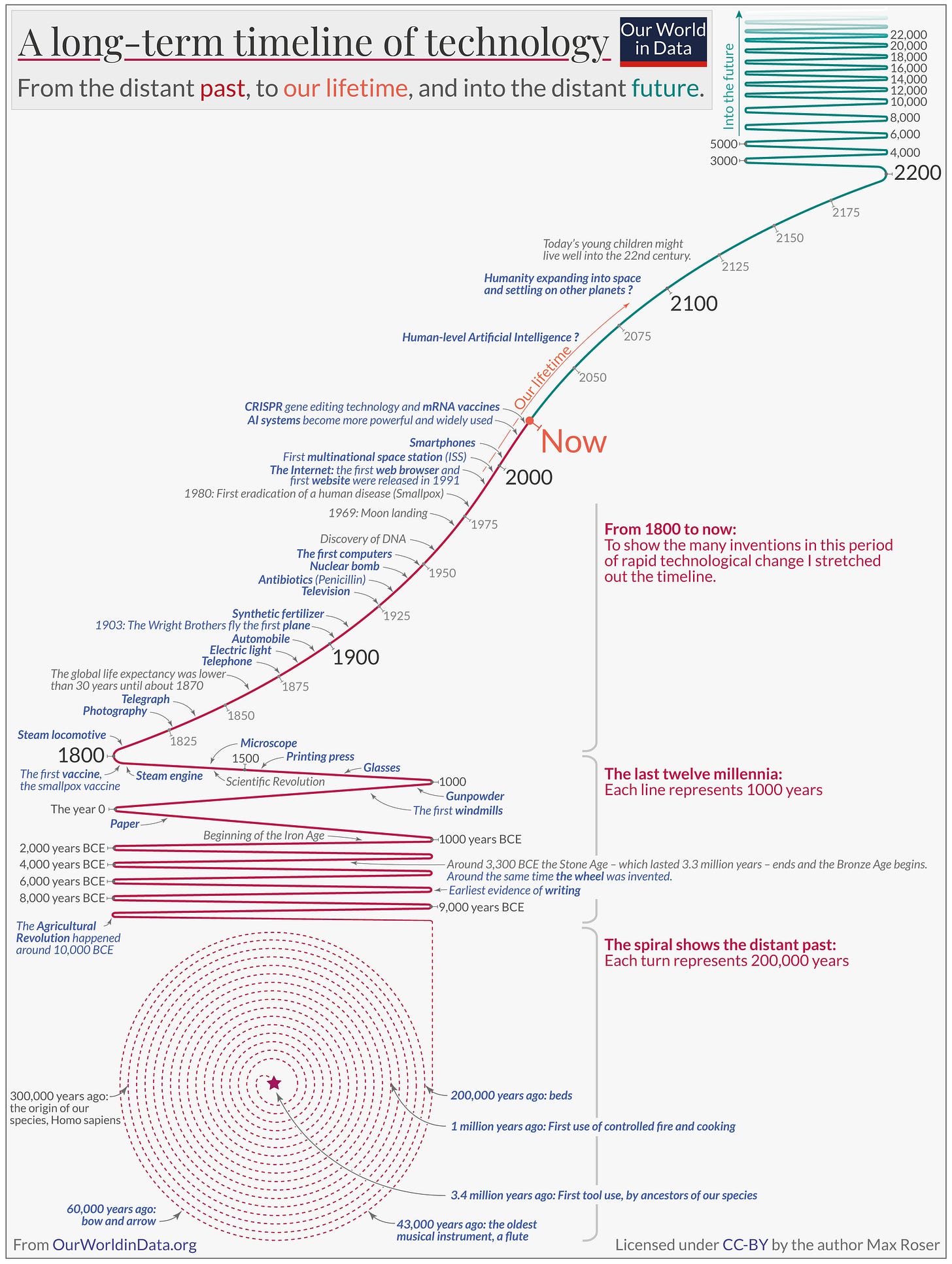

Today, those gaps have collapsed. Major technological shifts now arrive within years, sometimes months. Each new tool accelerates the arrival of the next. These improvements led to a Cambrian explosion in innovation over the last century compared to those prior:

For most of the modern tech era, speed has been the defining advantage of startups. Products that took decades to build can be stood up in dramatically less time with a fraction of the resources it would have taken before. Big companies moved slowly by design. Decision-making was layered, product cycles were long, and coordination imposed friction.

Startups, by contrast, were small and unconstrained. They could move quickly, test ideas, and pursue opportunities long before incumbents could respond. That asymmetry allowed new entrants to form entirely new categories while established players optimized what already existed.

That advantage is eroding.

With the tech environment we find ourselves in, there has never been a better time to build technology. The conditions for turning ideas into reality have changed. Compounding improvements across multiple layers of the stack have reshaped what is possible.

Stepan, the CEO of stablecoin fintech Squads, had this to say about building products with AI in 2026:

“We treat developer latency like product latency. Build times, review cycles, deployment friction are all first-class metrics. Engineers own features, not bugs. Agentic tooling handles triage and fixes. Engineering scales like an army. UX is architecture, not polish. Click latency and animation performance ship with the MVP, not after.

We optimize for flexibility over attachment. If stripping a system to fundamentals compounds quality and speed, we do it. The rules of building software are being rewritten every few months. Everyone’s a beginner right now. That’s not a threat if you’re lean and willing to learn. It’s an advantage. We’re excited to keep figuring out what it means to build great software in this environment.”

This is a structural compression of cost, labor, and coordination.

Everything in technology is being reset closer to the starting line. Nearly every developer is using AI. Products can now be stood up in dramatically less time with far fewer resources. The constraints that once protected incumbents are weakening, while the tools available to builders continue to compound.

Advances in AI have collapsed development cycles. What once required large teams, specialized expertise, and years of iteration can now be built by small groups in a fraction of the time. Tasks that previously demanded hundreds of engineers can be handled by a handful of people with the right tools. The ability to move fast is no longer scarce.

GitHub Copilot users also report task completion up to ~55–81% faster compared to traditional workflows, and Claude is helping developers produce years’ worth of work in a matter of hours…

Everything is changing…

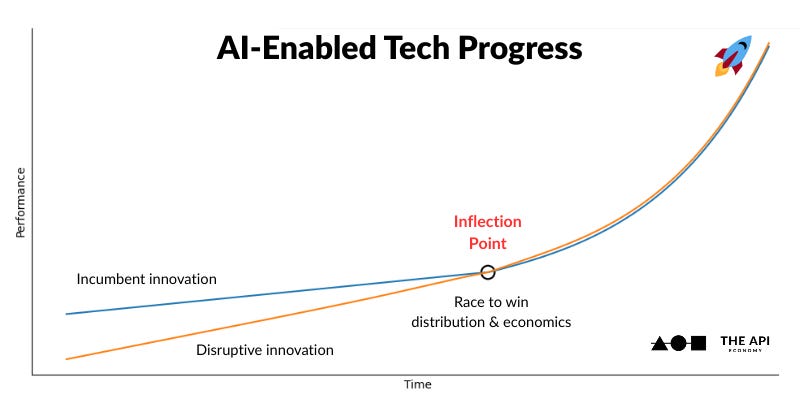

In this new landscape, two factors matter more than ever: distribution and economics.

First, distribution determines who can capitalize on momentum. Companies with existing reach can observe which products or features are gaining traction and deploy comparable offerings at scale with unprecedented speed. This compresses the window in which startups can rely on novelty alone.

To stay ahead, new entrants must iterate relentlessly and establish clear differentiation before incumbents can absorb the signal.

Every time a new feature in tech finds product market fit, it’s going to be a space race to see who can grow adoption, distribution, and economics the fastest between incumbents and startups.

Second, economics enabled by AI tooling are allowing smaller teams with fewer resources to compete at a much larger scale. Now, small teams are able to strip products down to their fundamentals and rebuild them with dramatically lower cost structures than ever before.

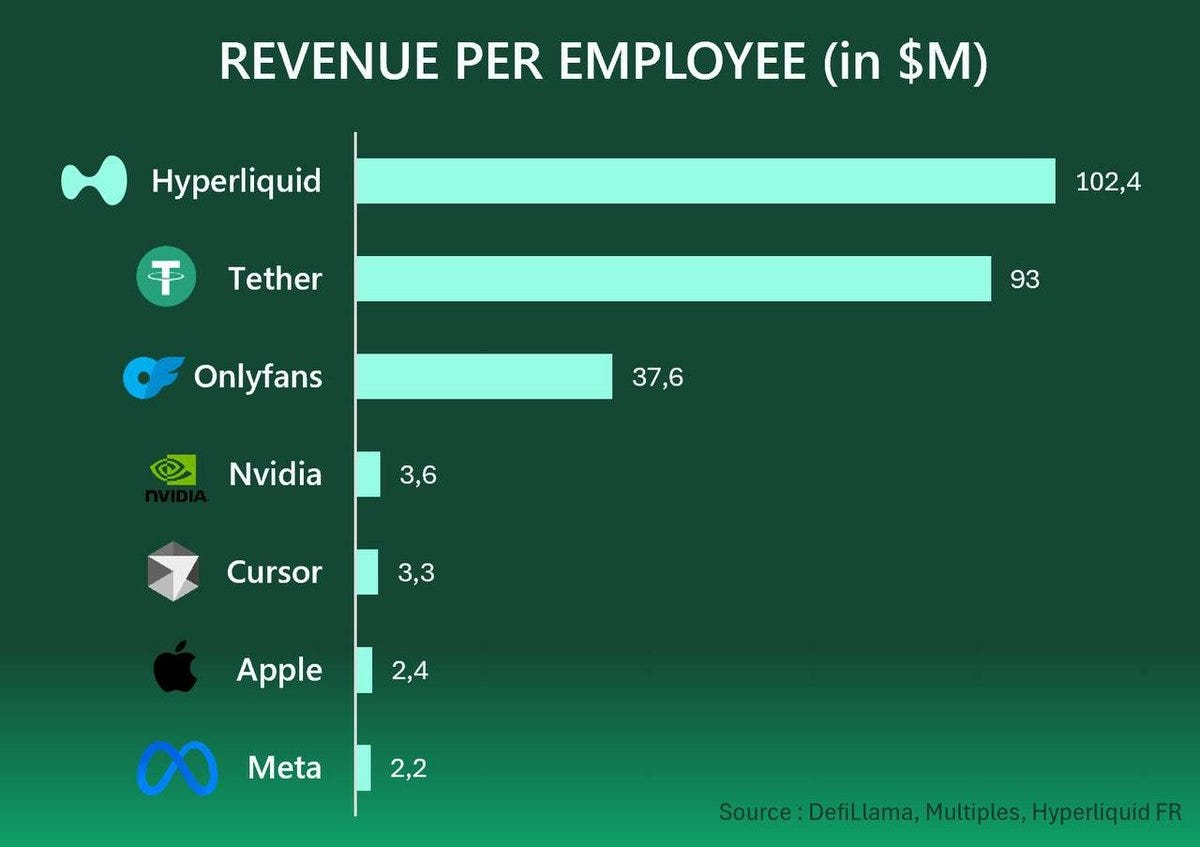

For example, when comparing revenue per employee across companies, modern, AI-enabled, and asset-light businesses often exceed legacy incumbents by a wide margin, illustrating how small teams can generate outsized impact relative to their size.

We are already seeing this play out. Companies like Tether, Hyperliquid, Cursor, and others are demonstrating how focused teams, modern tooling, and disciplined scope can produce an outsized impact compared to some of the biggest tech companies in the world on a revenue per employee basis.

This is a structural shift in how much leverage a small group can exert when competing with the giant companies that exist today.

Although we need to keep in mind that building products isn’t enough. You still need to be able to market them, sell them, and garner adoption of them. Big companies, for now, will continue to have a moat leverage by multi-year contracts, customer tech-debt, and other factors.

But these defenses won’t hold forever.

There are cathedrals everywhere for those who can see them. Not because the world lacks problems, but because the tools to solve them are compounding faster than the structures that resist change.

Building Spacecrafts In Days

It has never been easier for a small group of people to change how an entire industry works, whether at a startup or within a big company.

Innovation now compounds through speed, iteration, and leverage. What once required massive coordination and capital can now begin with a few people, modern tools, and a clear point of view. The distance between idea and execution continues to collapse.

This compression is why disruption feels relentless. Systems optimized for stability struggle in environments that reward movement. Platforms designed for extraction eventually expose themselves to replacement. The faster technology advances, the shorter the lifespan of complacency becomes.

Enduring companies will not be defined by how long they dominate a category. They will be defined by how often they are willing to rebuild themselves. They invest in platforms instead of features, prioritize speed over certainty, and treat reinvention as a constant rather than a crisis.

The barriers that once protected incumbents are eroding. The tools that once belonged to the few are now widely available. Many industries persist out of habit rather than necessity.

We are no longer constrained by what is possible, only by what we choose to build. When you can assemble the equivalent of a spaceship in days, the advantage belongs to those who move first, learn fastest, and refuse to wait for permission.

The cycles are compressing.

The window is open.

Until our next adventure.

Disclaimer: This month’s edition of The API Economy has no direct affiliation with Circle or any other company mentioned. I am employed by Circle at the time of this writing, but the views in this essay are my own personal opinions and don’t necessarily represent the views of Circle.

*Special thanks to Mama Schroeder for editing this essay (any typos are on her 😊).

I appreciate the optimistic view of AI enabling the little guys to innovate, and to compete with speed to market, rather than consolidating power to the big players. Also love that you used George Washington crossing the Delaware, very based.